The directory «Plots»

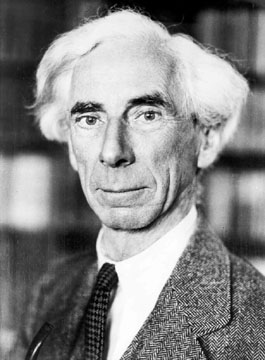

Russell Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3d Earl

(1872–1970)

British philosopher, mathematician, and social reformer, b. Trelleck, Wales.

Life

Russell had a distinguished background: His grandfather Lord John Russell introduced the Reform Bill of 1832 and was twice prime minister; his parents were both prominent freethinkers; and his informal godfather was John Stuart Mill. Orphaned as a small child, Russell was reared by his paternal grandmother under stern puritanic rule. That experience powerfully affected his thinking on matters of morality and education. Russell studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (1890–94), where later he was a fellow (1895–1901) and a lecturer (1910–16). It was during this time that he published his most important works in philosophy and mathematics, The Principles of Mathematics (1903) and, with A. N. Whitehead, Principia Mathematica (3 vol., 1910–13), and also had as his student Ludwig Wittgenstein.

World War I had a crucial effect on Russell: until that time he had thought of himself as a philosopher and mathematician. Although he had already embraced pacifism, it was in reaction to the war that he became passionately concerned with social issues. His active pacifism at the time of the war inspired public resentment, caused him to be dismissed from Cambridge, attacked by former associates, and fined by the government (which confiscated and sold his library when he refused to pay), and led finally to a six-month imprisonment in 1918. From 1916 until the late 1930s, Russell held no academic position and supported himself mainly by writing and by public lecturing. In 1927 he and his wife, Dora, founded the experimental Beacon Hill School, which influenced the development of other schools in Britain and America.

He succeeded to the earldom in 1931 and in 1938 began teaching in the United States, first at the Univ. of Chicago and then at the Univ. of California at Los Angeles. In 1941 he went to teach at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pa., after his appointment to the College of the City of New York was canceled as a result of a celebrated legal battle occasioned by protest against his liberal views, particularly those on sex. These views, much distorted by his critics, had appeared in Marriage and Morals (1929), where he took liberal positions on divorce, adultery, and homosexuality. In 1944 he was restored to a fellowship at Cambridge. In 1950 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Prior to World War II, in the face of the Nazi threat, Russell abandoned his pacifist stance; but after the war he again became a leading spokesman for pacifism and especially for the unilateral renunciation (by Great Britain) of atomic weapons. In 1961 his activity in mass demonstrations to ban nuclear weapons led once more to his imprisonment. He organized, but was unable to attend, what was called the war crimes tribunal, held in Stockholm in 1967, presided over by Jean-Paul Sartre, and directed against U.S. activities in Vietnam. Almost until his death he was active in social reform.

Philosopher and Mathematician

Throughout his life his dissent had scorned easy popularity with either the right or the left. Untamable, he had profound trust in the ultimate power of rationality, which he voiced with an undogmatic but quenchless zeal. Philosophically and ethically Russell’s thought grew in reaction against the extremes he encountered. He answered the idealism of F. H. Bradley and J. M. E. McTaggart with a logical atomism founded on a rigorous empirical base: he was deeply convinced of the logical independence of individual facts and the dependence of knowledge on the data of original experience. His emphasis on logical analysis influenced the course of British philosophy in the 20th cent.

One of his most important notions was that of the logical construct, the realization that an object normally thought of as a unity was actually constructed from various, discrete, simpler empirical observations. The technique of logical constructionism was first employed in his mathematical theory. Under the influence of the symbolic logic of Giuseppe Peano, Russell tried to show that mathematics could be explained by the rules of formal logic. His demonstration involved showing that mathematical entities could be “constructed” from the less problematic entities of logic. Later he applied the technique to concepts such as physical objects and the mind.

Although he came to have misgivings about logical atomism and never assented to all the propositions of empiricism, he never ceased trying to base his thought—mathematical, philosophical, or ethical—not on vague principle but on actual experience. This can be seen in his pacifism as well as in his philosophy: he objected to specific wars in specific circumstances. So, in the circumstances preceding World War II he could abandon pacifism and, following the war, resume it.

Similarly, in ethics he described himself as a relativist. Good and evil he saw to be resolvable in (or constructed from) individual desires. He did distinguish, however, between what he called “personal” and “impersonal” desires, those founded mainly on self-interest and those formed regardless of self-interest. He admitted difficulties with this ethical stance, as well as with his logical atomism. As much as anything, his thought was characterized by a pervasive skepticism, toward his own thought as well as that of others.

Social Reformer

As with his philosophical stance, Russell’s positions on social issues developed as a reaction against extremes in his own experience. He believed that cruelty and an admiration for violence grew from inward or outward defects that were largely an outcome of what happened to people when they were very young. Pacifism could not be effected politically; a peaceful and happy world could not be achieved without deep changes in education. “I believe that nine out of ten who have had a conventional upbringing in their early years have become in some degree incapable of a decent and sane attitude toward marriage and sex generally.”

His objections to religion were similarly based. What he tried to draw attention to was the destructiveness of accepting propositions on faith—in the absence of, or even in opposition to, evidence. “The important thing is not what you believe, but how you believe it.” The person who bases his belief on reason will support it by argument and be ready to abandon the position if the argument fails. Belief based on faith concludes that argument is useless and resorts to “force either in the form of persecution or by stunting and distorting the minds of the young whenever [it] has the power to control their education.”

If Russell’s logic was not always unassailable, his life showed that ethical relativism could be combined with a passionate social conscience, and that passionate commitment could be stated without dogmatism. In his autobiography (3 vol., 1967–69) Russell summarized his personal philosophy by saying, “Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.”

Comoren Islands, 1977, Nobel prize winners

Grenada, 1971, Bertrand Russell

Grenada, 1986, Statue of Liberty; Bertrand Russell

India, 1972, Bertrand Russell

Palau, 2001, Bertrand Russel

Paraguay, 1977, Medal of Nobel prize of Literature

Sao Tome e Principe, 2010, Bertrand Russell, Arthur C. Clarke